Clancy: A Critique on Fame Live from the Sold-Out Arena Tour

Twenty One Pilots isn't indie anymore, and Tyler Joseph took that so personally.

With the studio record, artists no longer have to consider how they’d perform their music live. Each album can now be staged for the most common place to enjoy it: the home. Either through a speaker, CD/record player, and/or headphones, music recordings have become optimized to be as close to our eardrums as possible.

Twenty One Pilots, however, go against the grain. Whereas many artists are opting for a more minimalist sound, the band’s newest album Clancy is designed with a fully-rendered vision of how the band will perform it live. Almost every song is a large-scale production, complete with Josh Dun’s electric drum solos composed to keep the crowd’s momentum going, Tyler Joseph’s isolated vocals during “powerful” lyrics so that the audience can scream alongside him, and intros that are long enough to become recognizable and incite a crescendo of excited screams before the song begins. This, however, has unintended consequences on the album’s overall effect.

Clancy is an emotionally stunted record: Joseph and Dun are no longer indie cult leaders, but mainstream artists under intense pressure to meet the musical and lyrical expectations of their extremely large fanbase. They attempt to rekindle their appreciation for the indie scene they emerged from, but it all feels outdated, like they they’re too old to be playing with the same gear. They experiment with a Dookie-inspired pop punk (“Next Semester,” “Midwest Indigo”), but the lyrics forgo Joseph’s signature, wordy, spoken poetry style—it’s a simplified version that seems to appeal to a much broader audience. They try to capture to swagger of Blurryface’s “Stressed Out” and the 2017 indie rap/hip-hop scene (“Lavish,” “Backslide,” “Snap Back”). Overall, Joseph reckons with the fact that he now profits immensely from his own suffering, and the difference between writing “from the heart” and for a fanbase that expects him to openly discuss his struggles with anxiety and depression has become scrambled (“At the Risk of Feeling Dumb,” “Oldies Station”). Yet, having every song seem optimal for largescale performances undermines the record’s argument. How can the band yearn for the days when they played to a an intimate crowd if they record music that’s completely aware it’ll sell out stadiums?

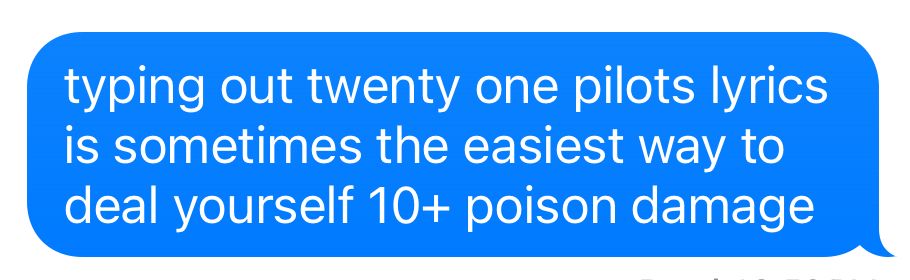

If Blurryface dealt with the band achieving cult status in the indie community, then Clancy feels a pressure that comes from an even bigger, more unexpected level of fame. “Overcompensate” tunes into the Twenty One Pilots radio station, mechanically flipping through staticky channels of broadcast snippets in different languages, only to settle on a fast-paced drum solo. The music is familiar: It has similar industrial beats, as well as an action movie energy captured in Blurryface’s “Heavydirtysoul” and Trench’s “Jumpsuit.” The songs “Backslide” and “Snap Back” mimic the same nonchalant, lo-fi hip-hop of “Stressed Out,” yet the lyrics are notably much angrier. In these, Joseph is no longer concerned with the drastic life changes caused by newfound fame. Instead, underneath his monotonous speech-singing, he expresses an acidic hatred for his fanbase (“Bite the hand that helps me, give it finger stitches” in “Snap Back”), people who encouraged Twenty One Pilots to embrace pop and sell out to become even more famous. While the best way to portray an emotionally stunted person may be to blame someone else for one’s inability to mature, the lyrics still contradict the message the listener hears. If the band doesn’t want to be involved with the flashy, almost-impossible demands of stadium touring culture, then Dun and Joseph didn’t have to compose “Overcompensate” as an imagined introduction to their live set. In the bridge of “Snap Back,” Paul Meany, Clancy’s producer, didn’t have to edit Joseph’s vocals to make it sound like he’s singing through a microphone booming to the back corner of Madison Square Garden, all while an ethereal chorus (eerily sounding like a concert crowd) ‘-ooh’s’ behind him. The lyrics, while still trying to maintain the tortured spirit of Joseph’s mind, have become less wordy altogether. It’s no longer a ritual to sit down, listen to the songs on repeat, and memorize the complex (albeit sometimes cringe) spoken-word poetry. From a fan’s perspective, one of the most important parts about becoming a part of the “Skeleton Clique” (yeah that was the fanbases’ title) is no longer there. So to argue that this is an album that attempts to recultivate the spirit of that lively, dedicated fanbase is contradictory to what the band actually does on Clancy.

Clancy gives the listener a behind-the-scenes perspective of the relationship between the band’s music and their fame. In some tracks, these result in fun, satirical critiques on the industry (“Lavish”). In others, however, they end up feeling like hollowed-out versions of their predecessors. “Paladin Strait” begins with a calming strumming of the guitar that develops into an epic, drawn-out, synth and drum duet, with Joseph projecting his falsetto into the distance. The track strikes a balance between the hardness of Dun’s rumbling drums and the softness of Joseph’s guitar and vocals—a sound design that intends to take the listener back to the days of “House of Gold” (Vessel) or “We Don’t Believe What’s On TV” (Blurryface). Yet, in both Vessel and Blurryface, Dun’s and Joseph’s instruments had dialogue—they clashed against each other and gave the song an interesting texture—and one could actually listen to the intimacy between the two bandmates. They had a private sensibility that songs like “Paladin Strait” lack. Instead, the spacious quality of the synths, the slight reverberation in Joseph’s vocals, and the buildup of the horns (played by Dun!) makes the final Clancy song feel incredibly public. If Joseph and Dun gave their millions of fans access to their relationship, then it makes sense that their sound evolved into something that encourages audience participation.

It's refreshing to see a technically skilled band that is cognizant of the magic of a live band, especially when other artists seemed to have abandoned live instruments altogether. Yet Twenty One Pilots is right: If their branding demands the spectacle of a sold-out arena tour, then they can’t go back to their indie roots, no matter how hard they try. To become indie again would mean defying all conventions and potentially isolating a lot of the fanbase who tuned in after Blurryface, and that’s not something Twenty One Pilots wants to do. The concerns outlined throughout the record ultimately don’t make sense because the band isn’t trying to innovate within the indie scene anymore. It’s giving into the industry completely; it’s begrudgingly repeating the same music (but worse lyrics) from Blurryface because that’s what got the two uber-famous in the first place.

Header image credited underneath the photograph. Lyrics were provided by Genius. Text message was a screenshot by author and reformed Twenty One Pilots girlie.

Disclaimer: There’s a whole fictional narrative about an oppressive dystopia played out in Twenty One Pilots’ music since Trench (if you see “Bandito” or “Nico” or “Trench” in the songs, it’s referencing the lore). I literally don’t care about any of that. That’s not what early 2010s indie pop punk/emo band Twenty One Pilots is to ME.

Of course I was going to write about the new Twenty One Pilots album. Nobody thinks what I think! #JusticeForLavish